As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the very first hmv store on London's Oxford street, come with us on a journey through the last century with a long read about our very long history...

As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the very first hmv store on London's Oxford street, come with us on a journey through the last century with a long read about our very long history...

In the beginning…

It may be a full century since the first hmv store opened at 363 Oxford Street in London, but our story actually goes back even further than that – in fact, you could say that our story really begins on May 20 1851 in Hannover, Germany, with the birth of a man named Emile Berliner.

Born to a Jewish merchant family, Berliner originally trained as an apprentice merchant with the intention of following in his father’s footsteps, as well as working as an accountant to make ends meet, but Berliner’s real passion was as an inventor. Over the course of his life, his various inventions would include a new type of loom for the textile industry, an acoustic tile, and even an early incarnation of the helicopter. But none of those inventions would be his most famous.

After moving to Washington, D.C in the United States in 1870 to avoid being drafted into the Franco-Prussian war, Berliner began pursuing an interest in new audio technologies such as the phonograph, a Thomas Edison invention that was an early forerunner to the vinyl turntables we use today, using a wax cylinder rather than a disc as the medium of recording sound.

Edison and Berliner subsequently became embroiled in a lengthy legal dispute when one of Berliner’s patents, a design for a new type of microphone to be used as a telephone transmitter, was ruled to be invalid by the United States Court of Appeals, effectively handing ownership of the design to Edison.

Undeterred by the legal setbacks, however, Berliner relocated to Boston and began working for the Bell Telephone Company. During that time, Berliner began experimenting with new methods of recording and reproducing sound, eventually gaining a patent in 1887 for his latest new invention; the Gramophone.

(Berliner Gramophone, c. 1899)

The first machine to use discs as the means of recording sound (although various materials were trialled before settling on the vinyl format used today), early versions of the Gramophone manufactured under the names ‘United States Gramophone Company’ and then ‘Berliner Gramophone Company’ used a hand crank to power the turntable. Eventually, though, Berliner partnered with an engineer from Camden, New Jersey named Eldridge R. Johnson, who helped design a wind-up motor to perform this tedious task automatically.

At the turn of the 20th century, Berliner and Johnson established the Victor Talking Machine Company to manufacture the improved Gramophones in the US, while a European affiliate, The Gramophone Company (which would become hmv’s precursor) was established in London by a business contact of Berliner’s named William Barry Owen.

Born in 1860 in Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts, Owen was originally sent to London by Berliner to establish a new European headquarters for their expanding business and ended up serving on the board of The Gramophone Company until 1906. Owen played a key role in establishing the UK’s recording industry – you might even call him its first-ever employee – but he would also play an even greater role in hmv’s history by helping to establish its most iconic trademark.

Enter the Dog…

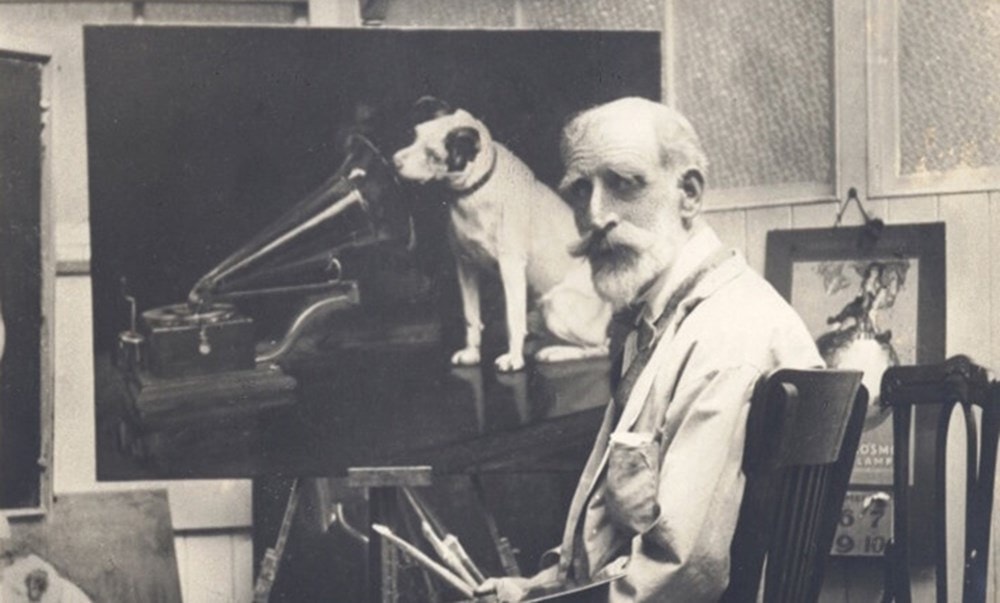

Looking to decorate the offices of their new London headquarters, Owen came across an intriguing painting by an English artist named Francis Barraud. Originally created in 1895 and given the unflashy title ‘Dog looking at and listening to a Phonograph’, Barraud’s painting depicted a terrier staring quizzically into the horn of one of Thomas Edison’s earlier machines. Ironically, given its subsequent history, shortly after its creation Barraud had contacted the Edison Company asking if they would like to use the painting in advertisements – for a modest fee, of course - but received a somewhat frosty response:

“Dogs don’t listen to phonographs.”

Instead, Barraud went to The Gramophone Company and his painting eventually found its way to Owen, who was struck by the image but immediately recognised a problem: the phonograph in the picture was manufactured by their biggest rival, so it would have to go.

In 1899, on behalf of the Gramophone Company, Owen offered to buy the painting on the condition that it was reworked to include one of Victor’s machines. For the princely sum of £100 (half for the painting itself, half for the exclusive rights), Barraud duly obliged and, later that year, delivered the reworked painting to its new owners, complete with a new title: ‘His Master’s Voice’.

Sadly, by that time, the painting’s original model had already met his demise.

Born in 1884 in Bristol and believed to be a Jack Russell / Fox Terrier cross, the dog featured in the painting had originally been owned by Barraud’s brother, Mark, who died three years later in 1887. Francis Barraud then took ownership of him for several years until handing him over to Mark’s widow, who would remain his owner until he finally passed away in 1895, shortly after the creation of Barraud’s original version of the painting. His final resting place is near her home in Kingston-upon-Thames, where he was buried in a small, Magnolia tree-lined park in Clarence Street.

Barraud’s dog was, by all accounts, a bit of a rascal; according to legend, the mischievous canine had a lifelong habit of greeting any new visitors to the house by running up behind them and biting at their heels.

So they called him Nipper.

The road to Oxford Street (via Hannover, Kolkata, and New Jersey…)

In 1907, construction began on a large manufacturing plant in Hayes, Middlesex, which would not only remain the company’s base of operations for decades to come, but would also become the site of the UK’s first-ever commercial record production facility. Though the building’s function would shift over the years (eventually becoming the headquarters of EMI as the company’s structure changed and evolved), the original copy of Francis Barraud’s iconic painting continued to hang in its boardroom until the building’s eventual closure and redevelopment many years later.

In 1915, construction was completed on a similar manufacturing facility in Camden, New Jersey, which would first house a factory producing Gramophones and speaker cabinets before eventually becoming RCA Victor’s headquarters, which it remained until the building was sold off and converted into apartments in 2004. Known colloquially as ‘The Victor’ or the ‘Nipper Building’, the building still stands today and, at the peak of its tower, features a large, round stained-glass window bearing Nipper’s image.

During the first two decades of the 20th century, the company grew rapidly into a global business, with not only the American and British offices but also a record pressing plant established in Berliner’s native Hannover in Germany, as well as expansions into other territories too, including a new pressing plant and recording facility in West Kolkata, India (which, as we’ll soon learn, would come to play a big part in an intriguing chapter of hmv’s history later on).

As early as 1901, the words 'His Master’s Voice' and images of Nipper had already begun appearing on records manufactured by Victoria in the US, and by the end of the decade had also been established as trademarks in the UK and Europe. Officially, though, the name of the label these records were released on was either ‘The Gramophone Company’ or one of its regional subsidiaries.

However, the trademark and the image of Nipper proved to be so popular that the label began to be referred to by the public as ‘His Master’s Voice’ or ‘HMV’, and eventually the name stuck.

So, on July 20 1921, at No. 363 on London’s Oxford Street, composer Edward Elgar presided over the official opening of the company’s new flagship showroom and the very first His Master’s Voice store opened its doors to the public, paving the way for the next 100 years on the high street.

The Roaring Twenties, Abbey Road, and noisy neighbours…

The first decade of hmv’s century on the high street coincided with an unprecedented period of economic growth which saw sales of ‘luxury’ electrical items boom dramatically. Under the Oxford Street store’s sub-banner ‘Home Entertainment and Electric Housekeeping’, His Master’s Voice continued to develop and sell more advanced versions of its gramophones, as well as all manner of other electrical household items from fridges to vacuum cleaners. And of course, lots and lots of records.

The Hayes manufacturing plant continued to grow and expand too, with two new buildings added to the complex, and by 1929 the facility covered 58 acres and had become one of the town’s biggest employers, with over 7,500 on its payroll.

However, not everybody was thrilled by its progress. One of the area’s local residents was a young journalist, poet and author by the name of Eric Arthur Blair, who would later find fame and fortune as a novelist under his much more recognisable pen name: George Orwell.

Orwell considered the Hayes factory a particularly egregious example of what we might now call urbanisation, or ‘gentrification’, and was so irritated by its growing, looming presence in his neighbourhood that in 1933 he published a withering poem on the subject, titled On a Ruined Farm near the His Master's Voice Gramophone Factory, which contained the following verses:

The acid smoke has soured the fields,

And browned the few and windworn flowers;

But there, where steel and concrete soar

In dizzy, geometric towers –

There, where the tapering cranes sweep round,

And great wheels turn, and trains roar by

Like strong, low-headed brutes of steel –

There is my world, my home; yet why

So alien still? For I can neither

Dwell in that world, nor turn again

To scythe and spade, but only loiter

Among the trees the smoke has slain.

Unfortunately for Orwell, however, things weren’t about to slow down any time soon. At the turn of the 1930s, The Gramophone Company merged with Columbia Records to create a new, larger company named Electric and Musical Industries, or EMI, and set about expanding its UK facilities even further.

In one case this included a new Central Research Laboratory aimed at exploring further advancements in technology, such as Alan Blumlein’s new developments in what he called ‘binaural sound’ – later renamed Stereophonic sound – and His Master’s Voice began to develop machines that could reproduce music in stereo for the first time.

Not all of the innovations created there had purely musical applications, either. One of its later employees, an English electrical engineer from Nottinghamshire named Godfrey Hounsfield, would develop the technology to create the world’s first CT scanner, and was both knighted and awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his efforts.

Another new facility was about to open its doors in London too – one that would later become much more recognisable to the public. On November 12 1931, EMI Recording Studios opened its doors for the first time with a performance of ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ in Studio One, conducted by very the same man who had opened the first hmv store a decade earlier; Sir Edward Elgar. The studio would eventually become better known, however, by the name of its street location in North-West London: Abbey Road.

New genres in Africa, a really big fire, and war…

Ever hear the one about the Indian who went to Africa and accidentally started a whole new genre of music?

No, that isn’t the set-up line to a terrible joke – it’s actually the outline of one of the most unlikely success stories in hmv’s history, and it begins at the hmv recording facility in Kolkata, India, with a man named P.B. Vatcha.

From the 1920s and into the 1930s, hmv had continued to expand its roster of record releases beyond the staples of classical and popular music that had proved to be its most lucrative thus far, and by the late twenties had launched a series of label variations catering to different styles of music. One of these, the GV series, specialised in Latin American music, particularly Cuban rumba.

Having already established ties to Africa in the late twenties, with engineers from the Indian recording studio sent to capture three recordings of West African music in 1928, it became obvious that there was a large, untapped market not only for the discovery of new types of music, but for the distribution of it too.

Thus, P.B. Vatcha packed his bags for Africa, where he would spend seven long and often frustrating years travelling the continent as hmv’s permanent sales representative. By all accounts, Vatcha’s years in Africa were not as productive as he would have liked, trudging from radio station to record store armed with a case full of Cuban rumba music that nobody really seemed to want to listen to.

Accounts of what exactly happened next vary, but Vatcha was either about to give up on his mission and leave Africa or had already returned to India, when it became apparent that there was a growing demand for the GV series releases both in the Congo and in the main cities in Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania, where local DJs had apparently gotten their hands on some of Vatcha’s wares and begun playing it wherever they could.

Over the coming years and right into the 1950s, the Cuban influence grew and began to influence local musicians, who blended the rumba styles with their own to create a style known as Congolese rumba or Rumba Lingala, after the local language. Eventually, that would evolve into Soukous and Kwassa Kwassa, types of dance music that would later become hugely popular both across Africa and in France, and would influence a wide range of musicians as diverse as Orchestra Baobab and Vampire Weekend.

The rest of the 1930s was an eventful period back in London too. In 1934 hmv launched its first ‘show train’, which travelled the length and breadth of the UK showcasing its gramophones, records and other projects to the nation.

But then, in 1937, disaster struck and the hmv store on Oxford Street burned to the ground in a huge fire.

It took almost two years for it to be rebuilt, but was finally re-opened in 1939 by conductor Sir Thomas Beecham, with the brand new addition of a small recording studio that would soon play a big part in the history of British music.

By then, however, the nation had bigger problems. The dawn of the Second World saw the newly-reopened hmv store on Oxford Street designated as an air-raid shelter (thanks largely to its proximity to Bond Street tube station), while the Hayes factory and its employees turned their technical expertise to developing and manufacturing radio equipment for the war effort. In 1944, the Sales & Service buildings were hit by German bombs and had to be completely rebuilt.

Soon, though, the war would be over, and another exciting chapter in hmv’s story was about to begin.

The Birth of vinyl and the era of Rock 'n' Roll…

As peacetime ensued and nations began to rebuild, the hmv store on Oxford Street was once again buzzing with life, and in 1946 Nipper even made his very first appearance in a Looney Toons cartoon (albeit as the victim of a piece of moustache-based vandalism by Daffy Duck)

Two years later, in 1948, the first modern vinyl record as we know it today was produced, with a soon-to-be standardised speed of 33 1/3 rpm. By 1954, the company had a new chairman in Sir Joseph Lockwood, who would eventually wind down the production of gramophones in favour of ramping up production of the increasingly popular vinyl records.

In 1958, the small recording studio at 363 Oxford Street would receive its first famous client, with a young singer named Cliff Richard using the studio to cut one of his first demos, recording two songs; ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ and ‘Breathless’.

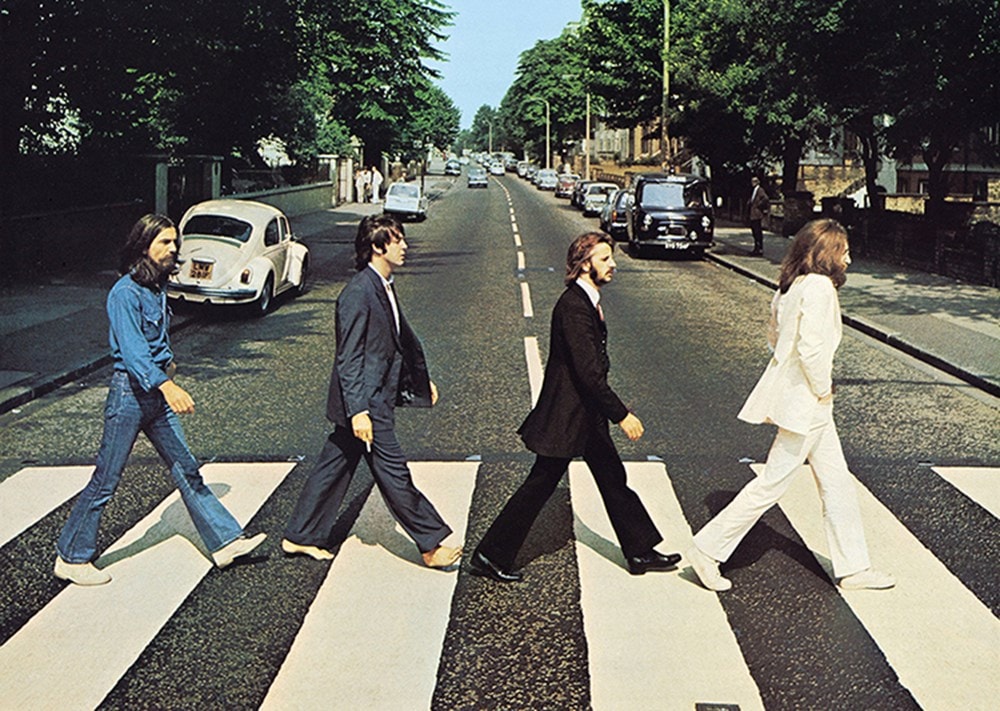

Then in 1962, the hmv studio at Oxford Street would play an important part in the careers of four young musicians from Liverpool who would go on to become even more famous than Sir Cliff.

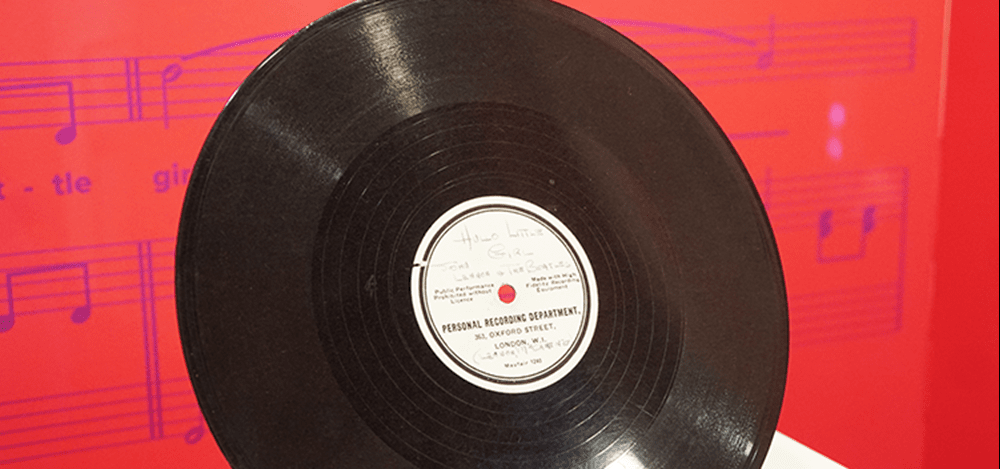

On New Year’s Day that year, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and a drummer named Pete Best arrived at Decca Studios in London to record a demo as part of an audition for its owners, Decca Records, arranged by their manager Brian Epstein. They recorded two songs ‘Hello Little Girl’ and ‘Til There Was You’, but Decca’s chairman, Dick Rowe, was unimpressed with the results.

In perhaps one of the most famously catastrophic errors of judgement the music industry has ever witnessed, Rowe declined to sign these four young men calling themselves ‘The Beatles’ with the immortal words: “Guitar groups are on their way out.”

Undeterred, Epstein took the audition tapes and headed to the recording studio at 363 Oxford Street, where he used hmv’s facilities to cut a single copy of the two songs The Beatles had recorded for Decca onto a 78rpm acetate, which he then took to a recording engineer and producer working at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios: George Martin. (The original disc, bearing Epstein’s handwriting, can now be found on display at The Beatles Story exhibition in Liverpool).

At a meeting on February 13 1962, Martin was presented with the disc and despite some initial doubts, eventually agreed to an ‘artist test’, recording a demo audition at Abbey Road on June 6 that year. It would be Pete Best’s first and only recording session with the Beatles at Abbey Road before he was replaced by Ringo Starr, but the band were eventually signed to EMI’s Parlophone label and the rest, as they say, is history.

As the Beatles rapidly grew into one of the world’s biggest bands, hmv began to grow too, expanding for the first time throughout the 1960s with 15 new stores opening across London and the South East of England. As for the hmv label, in 1967 it was converted into a label exclusively dedicated to classical music, with Nipper and his Gramophone now adorning recordings of the works of everyone from Mozart to Mendelssohn.

Turning 75, Three-day weeks, and Never Mind the Bollocks…

The 1970s began strongly enough with further expansion into new cities across the UK as new hmv stores opened up their doors to the public in Liverpool, Birmingham and Glasgow, and in 1973, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of The Gramophone Company’s formation, The Old Marlborough pub on London’s Carnaby Street was renamed The Dog & Trumpet and adorned with Nipper’s image.

Just a year down the line, however, the high street – and indeed the nation – was struggling. hmv was facing real competition for the first time by new upstarts Virgin and Our Price, but there were bigger problems on the horizon too. A combination of strikes and a gas shortage eventually led to the UK operating a three-day week to conserve resources, and at one point things had become so desperate for high street retailers that hmv’s Oxford Street store had to operate by candlelight.

Then in 1975, hmv – and Nipper – would face their biggest challenge yet, and almost disappeared from the high street forever. As part of a branding revamp, it was decided by EMI’s board to rebrand all of the existing hmv stores – except for 363 Oxford Street – from hmv to EMI Record Shops Ltd.

Whether it was competition from rivals, the public’s bigger financial woes, or the fact that people just really, really missed Nipper, by 1976 things had gone so badly that the decision was almost taken to close all of the stores except for Oxford Street. Thankfully, instead, the stores were all retained and converted back to the hmv brand, and with Nipper’s return, things steadily began to recover.

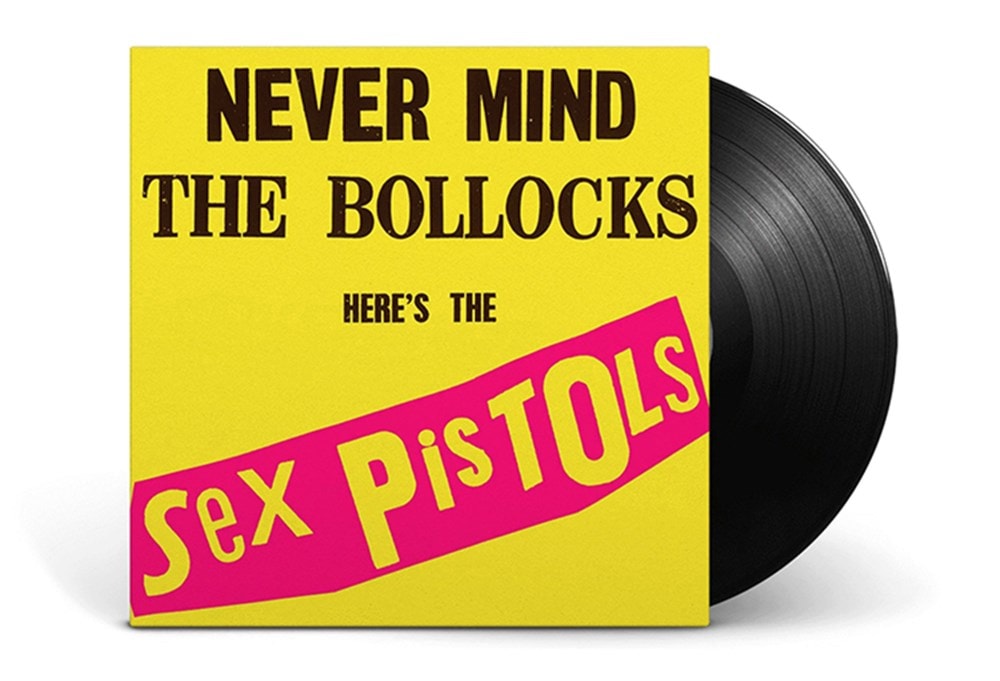

The following year then saw the arrival of a new and upcoming band who would spark the beginning of another eventful chapter in hmv’s history. On October 28 1977 the debut album from the Sex Pistols made its arrival on our shelves, and boy did it cause a stir.

The appearance of the album’s brightly-coloured sleeve bearing its title, Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, sparked outrage both in the media and in hmv’s stores, where customer complaints became so frequent that eventually, the word ‘bollocks’ had to be taped over by staff so that the album could remain on display. Boots refused to stock the album entirely, and in Nottingham, the manager of a Virgin Records store was arrested on obscenity charges for refusing to remove the album from the shelves.

The backlash against the album was so huge that it led to the creation of the Obscene Publications Committee, which would go on to ban the sale of all records by Crass, Dead Kennedys and others.

A new Nipper, a new format, and hmv goes solo…

The 1980s kicked off on a brighter note and in 1981 a nationwide search was conducted for a new mascot to represent Nipper, run in conjunction with newspaper The Daily Mirror. The winning dog, a Jack Russell cross named Toby from Doncaster, would go on to represent Nipper for the rest of the decade, serving in the role for nine years and meeting plenty of celebrities on the way.

In 1984, Toby’s owners even tried to enter him into the nation’s most prestigious dog show, Crufts. Sadly, Toby was disqualified on the grounds of having a “lack of pedigree.”

That same year, hmv also began to sell Compact Discs for the first time. The CD format had actually launched two years earlier in 1982, but EMI had been slow to adopt the format since it meant paying royalties to rivals Sony and Phillips. Eventually, though, EMI entered into a manufacturing agreement with Toshiba and in 1984 CDs eventually began appearing on hmv’s shelves.

Then in 1986, as part of EMI’s merger with Thorn, hmv and EMI finally went their separate ways, although the latter did retain a stake in the newly-established ‘HMV Group’. Later that year, hmv would enter the Guinness Book of Records for the ‘World’s Largest Music Store’ with the opening of a new flagship store at 150 Oxford Street, just down the road from where the first store opened in 1921, presided over by Sir Bob Geldof.

The new store ushered in an era of large-scale live events and signings – most of which went smoothly, although some did cause their fair share of chaos. A 1987 appearance at the store by teen pop sensations Bros attracted more than 5,000 screaming fans, who completely blocked off the whole of Oxford Street. The event had to be abandoned after 20 minutes and it reportedly took two hours to restore traffic flows to normal.

Another headline-making event that year involved Liverpool band Echo and The Bunnymen, who wanted to replicate The Beatles’ famous rooftop gig with one of their own on the roof at 363 Oxford Street. A small crowd gathered on the streets below and seemed to be enjoying the performance, but the police were not so amused and the band’s frontman, Ian McCulloch, narrowly avoided being arrested.

Going to New York, Going online…

The 1990s were a booming era for the music industry in general and the next decade would see hmv pass several new milestones, the first of which came in 1990 with the opening of hmv’s first store in America, at the corner of 86th and Lexington in New York City. Several more would open in the following years, including one at 72nd and Broadway and another in Times Square.

Back in the UK, meanwhile, hmv’s live events continued to make headlines when in 1992 an appearance at hmv’s Manchester store by Take That drew a 4,000-strong army of fans, and after the event, the band had to leave the building disguised as police officers in order to escape the crowds.

The following year saw another record-breaking feat with the opening of Level One in 1993, a dedicated space at the Oxford Street store which became the world’s largest computer games department. The event was even marked by the creation of a new game starring Nipper himself.

In 1997 hmv passed yet another milestone, opening its 100th store at Fort Retail Park in Birmingham, with the ribbon cut by Robbie Williams and the occasion marked by live performances from both Williams and Van Morrison. The following year, hmv also became the first music retailer to launch a transactional website, allowing music lovers to choose from over 250,000 CDs, cassettes and vinyl records to buy online.

As the next decade approached, however, the changing concept of ‘buying music online’ would present some of hmv’s biggest challenges yet.

By the end of the 1990s, the advent of the mp3 format and the rise of file-sharing sites such as Napster and Limewire had begun to present a threat to physical media such as CDs, and not just because of piracy. The advent of the cassette tape had already seen the 1980s and 90s become the era of the ‘mixtape’, and copying tapes from friends or even recording songs from the radio had long been part of the way music was shared.

It was also about convenience, though, and in 2001 Steve Jobs, the mercurial head of Apple Computers, launched the iPod, a product that would do for the mp3 what the Sony Walkman had done for the cassette many years earlier. For the music industry at large, even if it wasn’t immediately apparent, it would prove to be a game-changer.

The boom and the bust…

As the 21st century arrived, and despite the looming threat from new digital formats, the early part of the 2000s would become, much like the 1920s, a period of unparalleled economic growth for the economy at large and, for much of the following decade, hmv’s path followed suit.

There were some big changes, though, not least the closure in 2000 of the original hmv store at 363 Oxford Street as the store was relocated to slightly larger premises six doors down at No. 360, and George Martin’s path crossed hmv’s once more as he presided over the unveiling of a blue plaque commemorating the building’s history.

Two years later, hmv was floated on the London Stock Exchange and became a public company for the first time in its history. Continuing to expand and grow, hmv opened its 200th store in Galway, Ireland in 2005, and the following year even launched its own radio station to be broadcast internally across its 200 stores: Channel hmv.

A year later the first of a series of acquisitions would arrive with the purchase of book chain Ottakers, which subsequently merged with Waterstones to give hmv ownership

Then in 2008 came the global financial crash. High street retailers were some of the hardest hit in the chaos that ensued, with many long-established names such as Woolworths, who had once been a competitor, disappearing from view. Music retailer Zavvi, who had taken over the chain of stores previously run by Virgin, also retreated to an online-only presence as the harsh realities of the situation started to bite.

By this point, however, hmv was still large and resilient enough to ride the initial wave of fallout from the crash and even expanded further into the territory into live music, purchasing promoter Mean Fiddler and forming MAMA Group, which would run festivals such as Global Gathering and The Great Escape, as well as purchasing the Hammersmith Apollo.

Eventually, though, a combination of steadily falling sales of physical media due to the rise of downloading and the emergence in 2006 of Spotify and then other streaming services such as Netflix - as well as other economic factors such as rising rents and changes in UK tax law that dented the profitability of its online sales - all began to take their toll.

In 2011 hmv closed 40 of its stores and 20 Waterstones stores as it began to downsize, and the following year also sold the recently acquired Hammersmith Apollo and its majority share in MAMA Group. Finally, early in 2013, after more than 90 years on the high street, hmv collapsed into administration for the first time.

A false start and a new dawn…

As the last music retailer left on the high street, hmv’s collapse was one of the main topics across newspaper headlines and bulletins in the following days, but despite hmv’s most difficult period in its long history, it wasn’t over yet.

Venture capitalists and turnaround specialists Hilco purchased hmv in 2013 and one of its first big moves was a symbolic one. On September 28 2013, a newly-refurbished 363 Oxford Street, restored to look almost exactly as it did in 1921, opened its doors once again to the public in a ceremony presided over by Sir Paul McCartney, whose career the store’s recording studio had helped to kick-start so many years ago. hmv had come home.

More changes followed as the business re-shaped itself to fit the challenging new climate, with a decline in CD sales offset by a resurgence in the popularity of vinyl, which began its return to the shelves. A new, editorially-focussed website was launched and hmv once again began to focus on the live in-store events that had been such an important part of its history. A new transactional website, allowing music and film fans to buy online once again, followed in 2015.

As restructuring continued, hmv’s chain of Irish stores was closed, while its stores in Canada were closed down in 2017 and sold off to Sunrise Records, a Canadian record store chain owned by Doug Putman, who would soon return to play a much bigger part in hmv’s story.

While new stores were opened in various locations across the UK throughout the decade, there were some closures too, and although by the end of 2018 hmv’s stores were still profitable, Hilco took the decision that they were not the right owners to take hmv forward and in January 2019 placed the business into administration, and once again hmv’s future was on the ropes.

This time, though, it took less than a month to find a new owner. Doug Putman, who had taken over the Canadian stores two years earlier, saw an opportunity and in February 2019 purchased hmv from Hilco’s administrators. hmv was back again.

So is this the beginning of another 100 years? We’d like to think so, but who can say? Since the new owners took over in 2019 a new, flagship store – The Vault in Birmingham – has seen hmv break records once again by becoming the owner of the world’s largest music store for the second time, while the resurgence in vinyl’s popularity has seen hmv expand its vinyl range hugely over the last two years and its live events, now both in stores and venues across the UK, continue to be a big part of its appeal.

So what of the future? Why has hmv survived when so many others have fallen? Maybe it’s the public’s love of the brand, or of Nipper, or maybe its our people and their knowledge and passion for all things to do with music, films, TV and games. Maybe it’s in a sense of recognition that in the shift to listening to music online something has been lost; the aesthetics of a stunning piece of cover artwork, or the tactile joy of thumbing through the vinyl racks to find your next favourite record.

Challenges remain, of course, but as there are music lovers, film lovers and those who love to share those passions with others, and as long as hmv can continue to provide a space for people to enjoy those experiences, we think the future looks – and sounds – pretty good.